When French Communists Went on a Brutalist Building Boom

In the mid-20th century, a remarkable transformation unfolded in France as the country’s Communist Party embarked on an ambitious architectural endeavor, redefining urban landscapes through the lens of Brutalist design. This movement, marked by its stark, utilitarian aesthetics and emphasis on social utility, coincided with a period of political upheaval and industrial growth. As France grappled with the remnants of war and strived to modernize its cities, Communist leaders harnessed architectural innovation to embody their vision of collective welfare and egalitarian ideals. This article explores how this unique intersection of politics and architecture shaped the built environment, influencing not only the skyline of cities but also the daily lives of the citizens inhabiting them. From monumental public housing projects to civic spaces designed to foster community spirit, the Brutalist building boom stands as a testament to the enduring legacy of a fervent political ideology manifested through concrete and steel.

The Rise of Brutalism in Post-War France

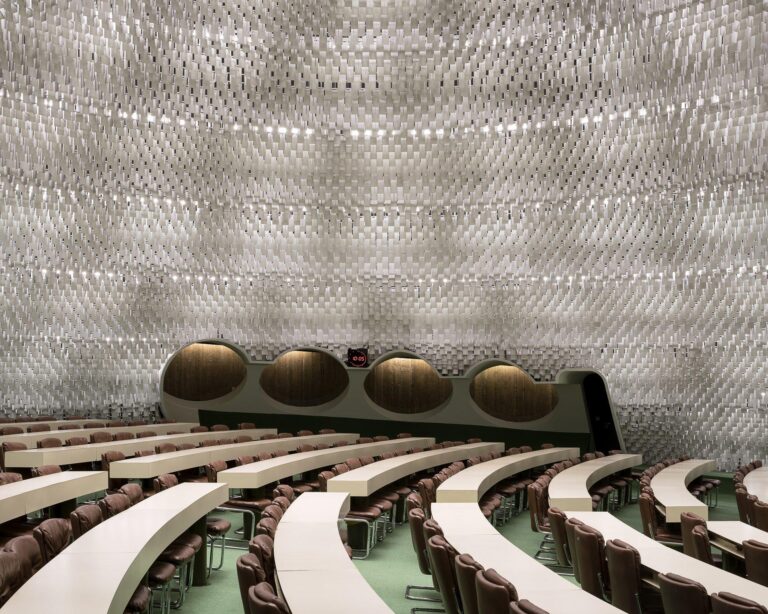

In the aftermath of World War II, France found itself at a crossroads of reconstruction and philosophical awakening. Architects and urban planners, influenced by the political climate, turned to brutalism as a means to express a new societal vision. The movement, characterized by its raw concrete structures and geometric forms, became a canvas for the socialist ideals espoused by the French Communist Party. This architectural style represented not only resilience but also a rejection of the ornate designs that had previously dominated the landscape. Cities like Marseille and the infamous UnitĂ© d’Habitation became exemplars of this bold aesthetic, embodying practical housing solutions that aimed to foster community and mobility.

Brutalism’s rise in post-war France was also marked by significant government support, as local authorities recognized the need for rapid urbanization and functionality. The architecture was not merely about aesthetics; it served a purpose that resonated with the citizens. Key characteristics of this movement included:

- Cost-effectiveness: Brutalist designs utilized inexpensive materials that facilitated rapid construction.

- Community focus: Buildings often integrated communal spaces to promote social interaction.

- Architectural honesty: Emphasis was placed on revealing materials and structure, showcasing the integrity of the design.

As ideology morphed into tangible structures across the landscape, the movement symbolized a burgeoning hope and a collective future post-conflict. This architectural renaissance, however, would later face criticism for its cold and imposing nature, challenging the balance between function and human-centric design.

Ideological Foundations of the French Communist Construction Wave

The ideological underpinnings of the French Communist construction wave were deeply rooted in a vision of social equity and collective ownership. With the disruption of the post-war period, communists sought to reshape urban landscapes not merely for aesthetic purposes, but to reflect their ideals of communal living and accessibility. Key tenets of this ideology included:

- Collectivism: Prioritizing community needs over individual pursuits.

- Functionalism: Design driven by practicality, focusing on the essentials of modern life.

- Affordability: Ensuring that housing and public spaces were economically accessible to all.

This architectural movement also embodied a rejection of traditional bourgeois aesthetics, favoring raw, unrefined materials that spoke to the brutalist ethos. The narratives behind these structures often emphasized their role as symbols of worker empowerment and societal transformation. The expansive projects implemented across urban centers were not only meant to house populations but to create a new sense of identity rooted in socialist values. An illustrative example of this commitment can be seen in the following table:

| Project Name | Location | Year Completed | Notable Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Les Arcades | Marseille | 1968 | High-rise social housing |

| La Cité Radieuse | Marseille | 1952 | Modular living spaces |

| Le Corbusier’s UnitĂ© d’Habitation | Marseille | 1952 | Vertical garden city |

Architectural Legacy and Urban Transformation

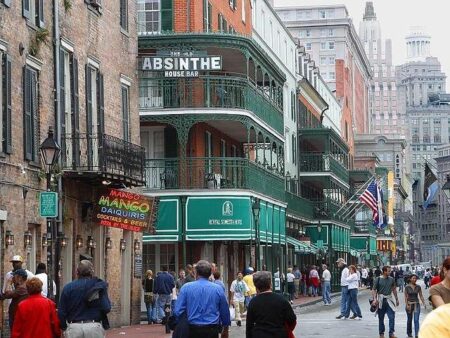

The architectural choices made during the French Communist era have left a notable imprint on cities across the nation. Characterized by their bold forms and utilitarian approach, Brutalist buildings reflect a profound commitment to social and political ideals. These structures not only symbolize an era of change but also delineate a distinct aesthetic that has sparked ongoing debate regarding their place in urban landscapes. While once heralded as a visionary expression of modernity, the monumental concrete blocks now face scrutiny as cities evolve and grapple with issues of functionality and aesthetic appeal.

As urban transformation continues, some cities are embracing the enduring legacy of these Brutalist edifices, recognizing their role in the narrative of public architecture. Initiatives aimed at preserving, repurposing, and integrating these structures into modern urban fabric are gaining traction. In some cases, this has led to a newfound appreciation, as communities seek to harness the historical value of these buildings while addressing contemporary needs. The table below highlights a few notable examples of landmark Brutalist structures and their current status in ongoing urban renewal efforts:

| Building Name | Location | Current Status |

|---|---|---|

| UnitĂ© d’Habitation | Marseille | Renovated as a cultural hub |

| Cité de Refuge | Paris | Active homeless shelter |

| Centrale Solaire de Cadarache | Cadarache | Converted to educational facility |

| Centre Pompidou | Paris | Ongoing modern art exhibits |

Lessons for Modern Urban Development and Housing Policy

The architectural choices made during France’s brutalist housing boom offer crucial insights for contemporary urban development. Brutalism, with its unapologetically raw concrete designs, prioritized function over form, reflecting a democratic approach to housing. Yet, as cities around the globe grapple with housing shortages, there are important lessons that can be extracted from this era:

- Affordability Matters: The historical emphasis on low-cost housing invites a renewed focus on accessibility in planning policies.

- Community Engagement: Successful brutalist projects often encouraged local input, illustrating the need to integrate community voices in modern development strategies.

- Sustainability: Many brutalist structures have exhibited lasting durability; current designs must similarly consider life-cycle sustainability.

Furthermore, the socio-political context behind the brutalist boom reveals the complexity of housing policies. The ambition to provide housing for all was intertwined with ideological beliefs, shaping urban landscapes in a unique way. Key takeaways from this include:

| Key Influence | Modern Application |

|---|---|

| Ideology-Driven Design | Policies should reflect social equity goals. |

| Mass Housing Solutions | Scale economics for efficient construction methods. |

| Enduring Aesthetics | Balance functional design with aesthetic value. |

To Conclude

In conclusion, the brutalist architectural movement in France, fueled by the aspirations of Communist policymakers in the mid-20th century, stands as a testament to the complexities of ideology and urban development. As we reflect on this unique chapter of architectural history, it becomes clear that these structures, often polarizing in their aesthetic, represent more than mere concrete and steel; they embody the social and political ambitions of a transformative era. While some view these buildings as relics of a bygone ideological struggle, others see them as vital components of the urban landscape that continue to provoke debate and inspire contemporary design. As cities evolve and grapple with their histories, the legacy of France’s brutalist boom serves as a reminder of the oft-contentious relationship between architecture, politics, and the public in shaping our urban environments.